“You gotta understand that back in them days [n-words] were pretty simple creatures. Give ‘em pork, some greens, some cornbread, and some poontang every now and then and they would work for you.”

-Mississippi prison guard, as told to Dr. Columbus Hopper in the 1960s

![]()

In 1960, Mildred Carter arrived at Parchman Penitentiary in Mississippi to visit her husband George Carter, a forty-two-year-old convict serving ten years for assault and battery. After driving up the long road to the prison and being searched by guards, she greeted her husband, and the couple walked to a small, rundown cabin in the prison yard.

The guards gave the couple privacy, so we don’t know what happened in the cabin. The couple may have held hands. George may have asked Mildred about their two daughters. They likely had sex. It was, after all, a conjugal visit.

Conjugal visits loom large in pop culture. They are the subject of prison-related jokes: In the sitcom Arrested Development, one episode builds to a scene where a character is pushed against a conjugal trailer and sees his incarcerated father having sex with his mother. They are also the subject of fantasies: Conjugal visits like the Carters are a popular setting for porn scenes.

Despite conjugal visits’ sultry reputation, however, reformers believe that more prisons should allow conjugal visits. They argue that conjugal visits are a smart policy that maintain inmates’ relationship with family and friends who will help the convicts stay out of prison and find a job when they are released. They prefer the term “family visits” and policies that give prisoners private time with their in-laws, children, and grandparents as well as their spouses.

When the Carters enjoyed a conjugal visit in 1960, Parchman Penitentiary was the sole prison in the United States that allowed them. Its history with conjugal visits began just after its founding in 1904.

The origin story of conjugal visits in America, however, is a chapter of American racism. In 1904, Parchman Penitentiary was a 19th century plantation recreated, with its black, convict labor force working in the prison’s cotton fields like slaves. Conjugal visits were a paternalistic, ad-hoc reward system. If black convicts worked hard, they got to have sex on Sunday.

Conjugal visits are a good policy, and they got their start in America for the worst possible reasons.

Working at Parchman Farms

Thirty years before Mildred Carter drove the long road to Parchman Penitentiary to visit her husband, hundreds of African-American women made the same trip. Some may have been visiting their husbands; the majority were prostitutes. They arrived every Sunday—the lone day when Parchman prisoners did not work the fields—on “a flatbed truck driven by a pimp as lordly as any who ride city streets in pink Cadillacs.”

Almost since Parchman’s founding in 1904, the guards had organized the arrival of prostitutes who had sex with inmates in the rows of Parchman’s cotton fields. The guards’ actions were not prison policy, but administrators tolerated the practice for decades.

This is the first documented case of conjugal visits in America, which the guards organized to increase productivity and exercise control over Parchman’s black, convict workforce. “You gotta understand that back in them days [n-words] were pretty simple creatures,” a prison sergeant told academic Columbus Hopper in the 1960s. “Give ‘em pork, some greens, some cornbread, and some poontang every now and then and they would work for you.”

It’s hard to imagine guards driving prostitutes into a prison for decades, but it occurred at Parchman because the penitentiary operated like a slavery-era plantation.

Parchman prisoners at work in 1911

After the Civil War, state governments in the south had responsibility for arresting, trying, and incarcerating black criminals for the first time. Most white southerners did not want African-Americans to be free, but they also did not want to pay to lock them up. Once federal control over southern states lessened at the end of Reconstruction, wealthy businessmen suggested a solution: convict labor.

As historian David M. Oshinsky chronicles in Worse Than Slavery, a lucrative and evil public-private partnership quickly developed in Mississippi. The judiciary purged juries of African-Americans, and legislators passed laws that obligated men who could not pay court fines to work in chain gangs. When there was unmet demand for slaves, as farmers often called the chain gang workers, arrests of black men increased. For crimes like stealing a pig, gambling, or being a tramp, the state sent them to work in the fields.

Initially, the state leased out black, convict labor to Mississippi’s farmers and construction crews. “The exclusive right to lease state convicts,” Oshinsky writes, “quickly became Mississippi’s most prized political contract.” Anger mounted among white men falling into poverty, who looked enviously at wealthy Mississippians raking in profits from convict labor. They could not tolerate having to sharecrop like black families. After this outburst of racism and populism, Mississippi politicians decided that black convicts would work for the state. Black convict labor built Parchman Penitentiary, and in 1904, thousands of them populated it. Ninety percent of the prisoners were black.

The new prison looked nothing like a prison and everything like a plantation. Parchman had no walls, towers, or checkpoints—only a barbed wire fence and wooden barracks for the convicts. The convicts worked 20,000 acres of fertile farmland six days a week. The guards and administrators lived on the grounds, and perks included inmates working as servants. The superintendent was a professional farmer who had no background in penal work. A newspaper at the time, according to Oshinsky, wrote that “His annual report to the legislature is not of salvaged lives. It is a profit and loss statement, with the accent on the profit.” Parchman Penitentiary is still better known in Mississippi as Parchman Farms.

Convicts’ lives were shaped by this imperative to increase cotton production.

Punishments were not standard. When the white guards whipped a convict for shirking work, or for no reason at all, the number and intensity of lashes depended on the guard’s mood and malice. Convicts often appealed to politicians for pardons, but they were rarely granted. Being unable to work was a surer path to a pardon, which led inmates to chop off an arm or cut their achilles tendon. Convicts could also win their freedom by becoming a “trusty,” a convict who helped control the other laborers in exchange for privileges like better food. The prison staff armed the trusties and gave a full pardon to any trusty who shot an escaping convict.

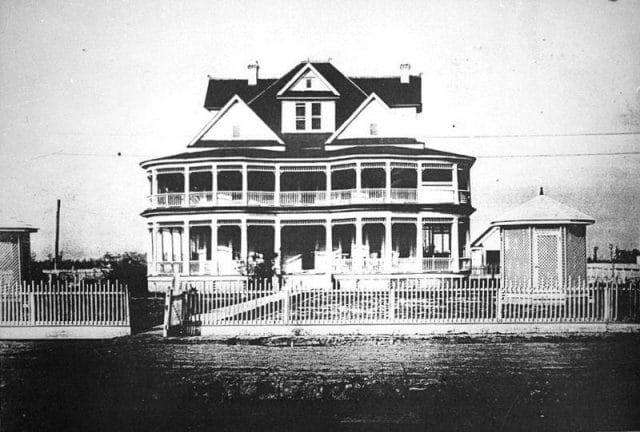

The superintendent’s house at Parchman

The trusties were part of a system of “paternalistic rewards” used to increase the productivity of Parchman’s workforce. Though for despicable reasons, this allowed Parchman prisoners to enjoy privileges that most inmates at actual prisons would never enjoy. The guards brought prostitutes to Parchman for convicts who worked hard in the fields, and eventually allowed wives to visit for the same reason. When convicts gambled, drank moonshine, or got high at night, guards looked the other way or profited from it. During World War II, the superintendent of Parchman even began allowing well behaved (i.e. hardworking) inmates to go home for the Christmas holidays.

Over time, the conjugal visits policy became more formal. By the 1950s, prostitutes no longer came to Parchman. The program was officially sanctioned, inmates met their wives and girlfriends in cabins they built, and the prison provided toys and focused on family. The tradition of inmates going home for the holidays also became an official furlough system. Paternalistic rewards had inspired humane practices.

By 1960, Parchman seemed to have a model, family-friendly visitation policy.

The Rise and Fall of Conjugal Visits in America

When Cook Knight visited Parchman Penitentiary in 1960 for Cosmopolitan Magazine and profiled George and Mildred Carter, the journalist wrote that “Parchman Penitentiary—with children and toys in its dining halls, inmates and their wives together every Sunday, and gates that open each winter to let prisoners go home for ‘vacations’—may well be the prison of the future.”

For a time, Cook was right. In the 1970s, new prisons were built with small rooms or cabins for family visits. Federal prisons have never allowed private visits, but as recently as 1995, 17 states condoned conjugal visits, often at the discretion of prison wardens.

The trend was toward America’s visitation policies resembling those found in much of the world. Most of Latin America offers conjugal visits. The Philippines historically has had prison colonies where convicts could live and work with their families. In Nordic “open” prisons, non-serious offenders shop, work, or study in town each day and can leave regularly to visit their families. Even conservative countries like Saudi Arabia and Iran allow spouses conjugal visits.

American prison reformers embraced conjugal visits for a simple reason: former criminals will be much more likely to stay out of prison if they have close friends and family. As Parchman Superintendent Bill Harpole explained in 1960, “In Mississippi, where a prison conviction is automatic grounds for divorce, families of convicts would fall apart if wives were not permitted the Sunday visit.”

The same logic applies today. In the United States, the recidivism rate is over 50%. In other words, the majority of inmates return to prison after their release. To keep former criminals out of jail, nonprofits and governments have launched programs ranging from prison reading and writing classes to re-entry programs that provide former convicts with job training. They also encourage prison visits.

Allowing prisoners to receive visitors is not just a nice privilege; it reduces crime rates.

“Visits from family and friends offer a means of establishing, maintaining, or enhancing social support networks,” write Grant Duwe and Valerie Clark of the Department of Corrections. When people leave prison, this can help them “from assuming a criminal identity” and find housing, jobs, and financial support. According to retired warden Arthur Leonardo, having “someone who loves you and will help you, and in the case of children, people who depend on you” is much more likely to keep former criminals out of prison than judges and the police.

But prison sentences stress relationships, and prison visits are not exactly therapeutic environments. Imagine trying to decide whether to stick it out in a relationship or suggesting a parent move into a retirement home—all while guards listen closely and police how long your hugs last. Referring to a television show where a wife talks to her imprisoned husband through a glass wall, George Carter told Cosmopolitan, “It would just about kill me to see my wife like that.”

Picture via Rennett Stowe

Prisoners who receive conjugal visitors clearly enjoy the sexual aspect. “Having that physical connection with your wife is heaven,” one prisoner told The Marshall Project. When researchers and administrators ask prisoners about conjugal visits, however, the convicts overwhelmingly say the most valuable aspect is intimacy. “Many problems were solved during the privacy and closeness of these visits that would have resulted in violent arguments and hard feelings,” one felon told a researcher who visited Parchman in the 1960s, “were these visits not allowed.” When a gay inmate in California won the right to conjugal visits with his partner, he told the press, “I got to spend 2 1/2 days one-on-one with my partner, my best friend, my confidant, my life partner. It wasn’t about the sex.”

This is why prisons prefer the term family visits to conjugal visits, and why the most permissive policies allow prisoners to spend a weekend in a small house on prison grounds with their children, in-laws, and grandparents as well as their spouse. Conjugal visits involve more family meetings than sex. Some prisons provide condoms, but they also stock board games.

Advocates suspect conjugal visits are very worthwhile. Data is scarce, but a study of a 1980 family visitation program in New York found that released prisoners who had conjugal visits returned to prison 67% less often. This may not be cause and effect, but it demonstrates the power of family ties and the promise of promoting them.

Despite their crime fighting, cost-saving potential, conjugal visits never fully took off in America. Administrators understandably restricted them to inmates with records of good behavior and did not allow them in maximum security prisons. Less understandably, they often only allowed family visits to first-time offenders who were so close to finishing their sentences that—as one critic pointed out about Parchman’s program—the inmates should probably have been out on probation or parole.

While 17 states had programs in 1995, today only three states—California, New York, and Washington—have meaningful programs. Four more states allow children or grandchildren overnight visits, but not spouses. New York has one of the most liberal visitation policies. Yet in 2013, New York only arranged a total of 8,000 visits between all its participating inmates.

When politicians and administrators oppose conjugal visits, they warn of families smuggling in contraband. (This does happen, although wardens who oversee conjugal visitation programs say it is manageable.) The expense of hosting prisoners’ families also leads to opposition, since any cost savings are long-term.

The decline of conjugal visits, however, is most motivated by public opinion and politics. Retired prison warden Arthur Leonardo has described the revulsion Americans feel toward prisoners. “There’s this feeling that we shouldn’t be doing anything for them,” he told The Marshall Project. Voters “get upset when they find out inmates get health care! Health care is a curse word!”

The same dislike Americans feel toward anything positive in inmates’ lives galvanized Richard Bennett, a state representative in Mississippi—which ended its conjugal visit program last year despite pioneering the practice—to push for a permanent ban. “You are in prison for a reason,” Bennett told the New York Times. “You are in there to pay your debt, and conjugal visits should not be part of the deal.”

In 2010, when the governor of New York earmarked $800,000 for the construction of two conjugal trailers at Five Points Correctional Facility, he faced similar opposition. “It is an outrage that Governor Paterson and the New York City Democrat legislators are moving forward with plans to… reward its most hardened criminals — criminals who have committed violent and serious crimes — with conjugal visits!” said a state senator in a statement widely covered by the press. “They want to spend more [taxpayer money] on luxuries for dangerous criminals!”

The Prison of the Future

When Doran Larson investigated an open prison in Finland, where prisoners live in dorms, work in town, and visit their families regularly, she wrote in The Atlantic about two reasons why such permissive policies exist in Scandinavian prisons.

One reason is that the professionals who run Scandinavian prisons face much less political pressure than administrators in the United States, some of whom are politically appointed. This insulates prison policy from politicians like Bennett and Paterson, who denounce conjugal visits or the granting of parole.

The second reason is race. Scandinavia has a relatively homogenous racial composition. Since most prisoners look like other Scandinavians, voters see inmates as people like them. In the United States, a majority white country where black and hispanic inmates make up a majority of the prison population, voters and officials with political clout are more likely to see prisoners as an unredeemable “other” that don’t deserve family visits, furlough, or basic rights.

Given how Parchman developed model policies despite its terrible history, it’s tempting to think that if family visits and furlough could work there, then they could work anywhere. America’s history with conjugal visits, however, shows this is not the case. And even in 1960, when Parchman was held up as model, it still had good policies for all the wrong reasons.

In 1960, the prison remained a place that segregated prisoners and worked its mostly black convicts hard in the fields. A federal judge later called the living conditions “unfit for human habitation” and working conditions an affront to “modern standards of decency.” In 1961, even as couples like Mildred and George enjoyed Sunday visits, state police imprisoned 300 Freedom Riders at Parchman. The guards—who had instructions from the governor to “break their spirit, not their bones”—mocked the Freedom Riders and stripped off their clothes and flooded their cells.

Freedom Riders; via Library of Congress

When Cosmopolitan Magazine profiled Parchman Penitentiary, its warden sounded like a model reformer as he argued that conjugal visits kept families together. The magazine, however, reported that holiday furloughs were reserved for “trusties,” and until 1972, trusties continued to maim and kill their fellow inmates in order to enjoy their privileges.

When a researcher named Columbus Hopper researched conjugal visits at Parchman in the 1960s, he discovered that the same racist sentiments and desire to maximize productivity still motivated the conjugal visit policy.“Oh, yeah, they are better workers,” a guard told Hopper. “If you let a [n-word] have some on Sunday, he will really go out and do some work for you on Monday.”

Criminologist Dr. Chris Hensley has studied conjugal visit policies. When he talks about it with prison officials, he has told The Economist, they laugh. It has a “deviant connotation,” he says.

If we want America’s dark history with conjugal visits to one day be redeemed, that has to change.

![]()

For our next post, we investigate a century of debates over pie charts. To get notified when we post it → join our email list.

![]()

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. You can follow him on Twitter here.

The lead image of Angola Prison was taken by Alan Lomax.